What is YOUR goal in this oneshot?

Before designing a one oneshot adventure you should think about what your goal is. Do you want to showcase a new system to your established group of players? Do you want to show some people without any role-playing experience what it is like? Do you want to provide a game of a certain mood (maybe Halloween or Christmas themed or one in homage to a movie)?

Some Examples

I will shortly showcase three oneshots I have run multiple times and what I designed them for.

- First we have a The Dark Eye (“Das Schwarze Auge” in German) oneshot that is supposed to introduce people without role-playing experience to this style of game.

The Dark Eye was chosen because it is a classic fantasy game and most people, i believe, still expect a TTRPG to be of the fantasy genre.

As this game was designed for absolute beginners there is a lot of prep involved. Expect that unless players are prompted to do something they will not do anything (pleasant surprises notwithstanding).

The players are provided with a limited choice of premade characters per player, each of which contains a description, a name, role-playing hints and all the stats and rules they will need on one sheet of paper. It is important to not overload your players here, be concise.

The game starts with a clear declaration of what the characters are supposed to do. They are supposed to perform in a play on a fair and the first scene is the planning of that play, directed by a NPC.

This is an invitation to learn the collaborative nature of the game as well as the acting aspect without any stress involved.

The second scene is an exploration of the fair. The importance here is the act of exploration by the players and the reward for it by a memorable scene with someone they encounter.

The third scene is the enactment of the play, here is the first time we use the rules of the game. Let the players make some skill checks and work them into the play, for example the player might need to make a check to punch someone in the play in a manner believable by the audience but non-harmful to the other actor. The focus here is to showcase how skill checks are woven into the narrative without the players stressing over whether they succeed or fail.

The scene ends with a twist when another actor, an NPC, is kidnapped. This signals that the real adventure begins now and heightens the stakes. The players are then prompted to follow the kidnappers and return the missing actor by the leader of the acting troupe and promised rewards for a safe return.

The players follow the kidnappers to a small farm that the kidnappers have taken over. Now the players can decide how to tackle this problem. They can try to negotiate a ransom, sneak in and free the hostage, try to break through the front door and fight the kidnappers etc. This scene should convey the freedom to tackle problems according to the strength of the characters and the planning as a group.

After the rescue you can either play or summarize the return to the fair and a celebration that follows. I usually use very simplified rules in this case because it is not the goal to teach the rules, since the players might not be interested in the long term and might even be turned off if the rules seem too complex and important. - A Call of Cthulhu one shot for Halloween is my second example. This game has the goal of introducing experienced role-players to a new system and tell a short story with a horror theme.

The game was inspired by a real life archaeological find and the surrounding events and persons. There are enough player characters for each player and maybe one or two backup characters, but the assumption is that most are part of the story or the ones not chosen are even used as NPCs. Each character is handed out with the character sheet and their background story.

The first scene is a social event that explains why the characters are together, why they are alone and provides a hint to the mystery later on. This scene gives the players time to acclimate themselves in the characters and learn who everyone else is. Shortly before the scene ends naturally it is interrupted by a shot being fired in the distance.

This is supposed to prompt the players to investigate or prepare for whatever is coming. Either way a grave robber who has been badly wounded comes to be in the company of our players. He carries a few hints to the mystery and can answer a few questions before becoming unconscious or dying, if no one tends to his wounds. This scene exists to increase tension and reward quick thinking on the players’ part.

Next the players will start to hear the noises of small animals that try to get into the house and start to crawl all over it. Depending on where the players fortify themselves the creatures, rat-things, will enter the house and swarm to a room containing some archaeological artifacts. This scene exists to create the feeling of the horror of being overwhelmed by monsters and the futility of standing in their way. At this point various bits of the histories of the characters become relevant and the players have to convey how these characters would act in this situation.

This culminates in a final scene at the dig site where the characters can witness and stop or take part in a ritual that leaves the places as history has recorded it. The rules used here should be the actual rules of the game but they do not need to be enforced rigorously as this is more a short stage play then anything else. - The last one is a Vampire: The Masquerade oneshot that focused on the player characters solving a murder mystery that had multiple layers.

On the top layer the murderer itself was to be found. On the second layer the players were to find out the motive for the murder and the last layer was to confront the people behind the murder.

This structure was chosen to demonstrate the potential for intrigue in V:tM games. The scenes of the investigation were set at larger than life locations in the city the game is set in, to get the players to be interested in a campaign there. The rules system was chosen as a very simple one that was provided by the publisher that allowed character creation in about 20 minutes without knowing the rules up front. The goal here was to “sell” a campaign to advanced players unfamiliar with the game or setting. Part of that is to showcase the freedom that a city based game provides by allowing the players to contact other people from their factions and following any idea they might have to solve the mystery.

How to construct a good premise?

The most important question to ask here is whether the events of the story are happening to the characters (passive) or if they are caused by the players (active). In the examples above the first and second start passive and switch to active after the twist. The third starts active as the players can pursue any leads they want. If you want to introduce role-playing to inexperienced people you might want to start with a passive premise. If you want to showcase what kind of freedoms a game is about you might want to start with an active premise.

How to construct a passive premise?

The group of player characters is somewhere where they are constricted in their movement, either physically (i.e. they are in a house in a blizzard) or socially (i.e. they have signed a contract to perform an action). The action in this case has to come from outside to the players and they have no way of escaping it (i.e. a snow monster comes into the house through the chimney and the blizzard is too deadly to risk the escape from the house) or is an escalation of the task at hand that they are forced to perform (i.e. while cleaning an old house they awaken a vengeful ghost). Before the inciting incident happens the players should get a short scene among themselves so they know each other’s characters unless not knowing the others is part of the premise.

How to construct an active premise?

Here we expect the actions of the players to drive the story, so either the characters have to be set up with strong motivations and clues how to fulfill those motivations or we have to build a small but strong setting that can accommodate their actions. Either way, starting active requires more work on the part of the GM and the players and is more suited to at least mildly experienced players. The players could be send to bring some freight from one place to another but they have multiple roads to choose from. Here it is important to make the choice meaningful i.e. on one road there are often raider attacks which increases the likelihood of combat and on another they will encounter customs officers with a dodgy reputation which will potentially lead to a difficult social situation and so on. The players should have at least be able to make deductions about the consequences their actions might have.

How to choose the rule-system?

Here the question is whether you want to introduce a specific rule set, you want to showcase a style of play or showcase a setting. You might want to run a oneshot to try out the newest edition of your favorite game before switching to it in your regular game. If you do not want this it is better to either use a limited rule set of the system you want to play (often there exist quick start sets for such cases) or to use a system that the players are already familiar with and just go for the feeling of the rules (i.e. use D&D rules and replace magic with vampire discipline powers to showcase Vampire:The Masquerade if your players never played anything else). The players should never feel that they have to learn a rule system for a single evening of play! You will have to guide the players through the rules as play progresses.

What is a good length for a oneshot?

In my experience oneshots take anywhere from three to five hours. Depending on your experience as a GM and the experience of the players and the rule system, the amount of different scenes that can play out in that time varies quite a bit. The trick here is to design scenes in a way that you can scale the time they take up or down depending your needs during play. For example let’s say you have a scene planned where every player character can talk to an NPC and it starts to take a bit more time than planned, maybe two characters are talking to the same NPC at the same time and you can shave off a few minutes and later on you give those players a bit more time and reduce the time of the others. A more radical approach is to ditch entire scenes by either cutting the adventure short and emphasizing the importance of early scenes or by cutting scenes out in the middle and setting the important details of these scenes in others. For example I have a scene in my Dark Eye oneshot that takes place while the player characters follow the kidnappers to provide a smaller encounter to get the players to solve a problem on their own. This can end in a fight with some hyenas or in the group sneaking around them but it is non essential to the story and can be cut if time runs short.

In my experience combat scenes pose a special difficulty because combat usually takes a long time in most systems and if you are unwilling to adjust the stats of the enemy NPCs you might not be able to end the combat early. One trick here would be to have a “cavalry” of sorts arrive to end the fight but this often leaves the players with a bad feeling. Another is to have the enemy flee or surrender when the tides of combat have turned enough in favor of the player characters.

My personal rule of thumb is that I can have one major and one connecting scene for each hour but this is very dependent on your style of play.

I would advise to start with two scenes that are the beginning and end of the session and place scenes in between that can contain information or things that also believably could be obtained in the last scene. This is important or else the scenes might feel like filler content if they do not connect to the main story.

After running a few shorter oneshots you will find your own rule of thumb and will have learned how to scale the story up or down.

Should you provide pre generated characters?

This depends again on your goals and your player base. If you know the players beforehand it might be possible to let them create characters with your help before the game day. If not, I would only allow character creation by the players if the used system allows this to be done in less than 30 minutes by the whole group or you will lose too much time and run into problems during the story. In general I only allow players to generate characters in oneshots where the players have a good grasp on the fitting character types or they can be inferred by the rules.

In most cases I would provide pregenerated characters but also provide enough that everyone has a choice of character. My way to do this is to create twice as many pregens as I expect players and hand each one two characters. They have first choice to either. Any character that is not chosen becomes available to everyone. This way no one should be left unhappy with their character.

If you have to have certain characters for the story to make sense, like in my Call of Cthulhu example, explain that to the players beforehand.

Do I need to end my oneshot in combat?

The reason many oneshots have a big fight in the end is because it is a fitting climax of a story, the big bad is identified and now the two sides do everything to win. But combat is not the only option. In a more investigative game a social gathering of the suspects and some verbal fencing and logical deduction might be just as exciting. Maybe the last scene is at the exit of a dungeon with a horde of monsters too large to beat on the tails of the heroes and their escape hinges on a puzzle. Maybe the last scene puts a moral quandary to the characters and the story ends with the consequences of their choice. So the short answer is no 🙂

Summary

In this article we have talked about the construction of a oneshot and how your goals influence the decisions you make when creating it.

I have given you a few examples of oneshot designs I have used in the past that had three different goals.

We have taken a look at active and passive premises and when each is appropriate to use and how to construct them.

Next we have taken a look at the decision making process regarding the rule system and whether you should use the full rules of the system you want to play, a quick start version or a different system familiar to the players.

We have taken a look at the timing of scenes in a oneshot and how to reduce the time of an adventure that threatens to take too long and how to construct an adventure in a way that makes it easier to scale it up and down for different time constraints.

We have talked about when it is appropriate to let players create their own characters, when you should provide enough characters to choose from and when it is acceptable to have just enough characters for each player to get one.

Finally we have talked about possibilities for the climax and seen that there are other options then combat as final scenes. I hope you have found this helpful.

If you use these methods I would be delighted to hear of your experiences.

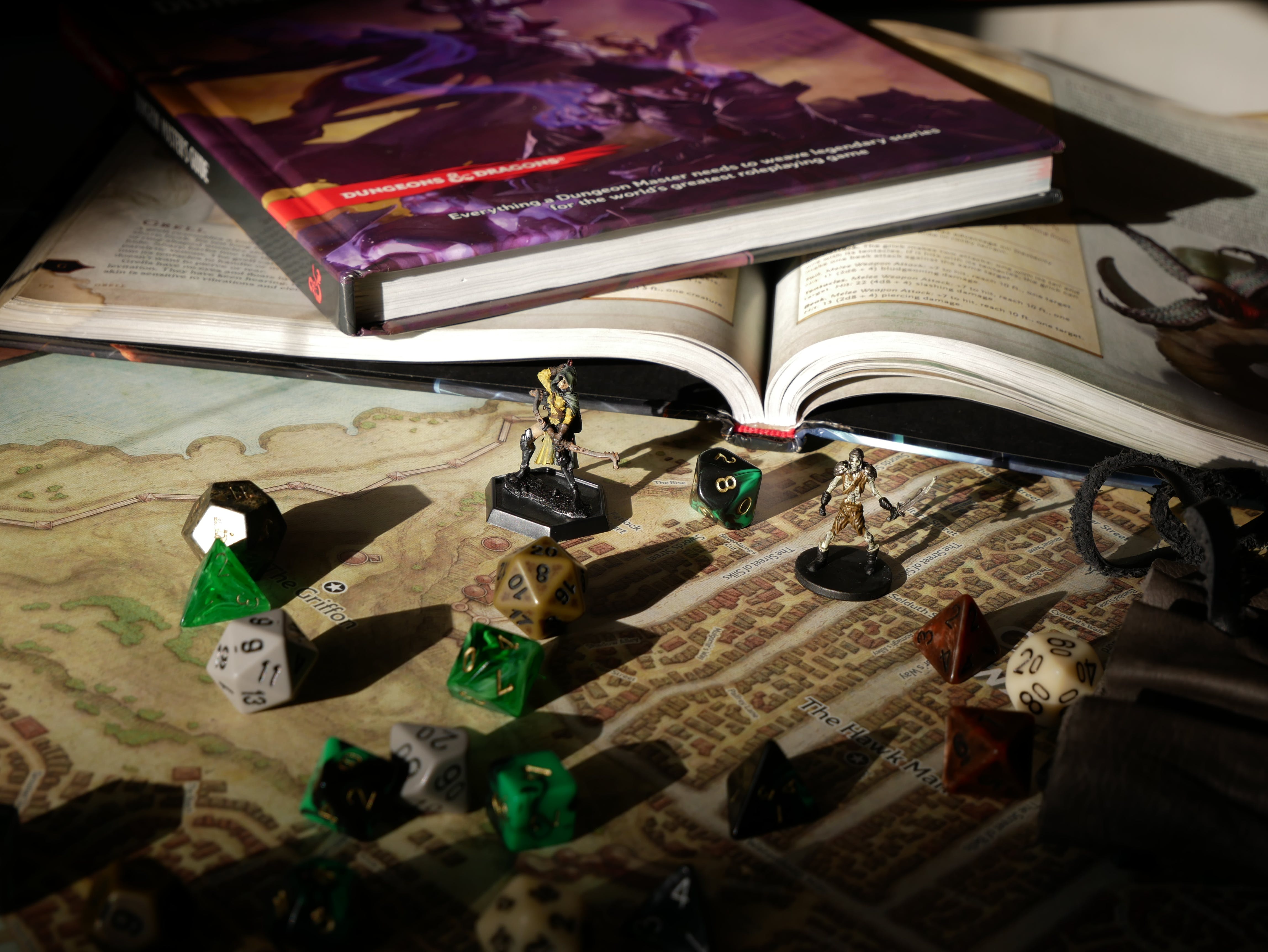

Images used:

https://www.pexels.com/photo/shallow-focus-of-clear-hourglass-1095601/

https://www.pexels.com/photo/bare-trees-surrounding-house-2827948/

https://www.pexels.com/photo/figurines-and-dice-on-board-game-map-7018123/

https://www.pexels.com/photo/6-pieces-of-black-and-white-dice-37534/

https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-group-of-people-wearing-sunglasses-9771812/

https://www.pexels.com/photo/three-people-standing-near-table-2981109/

All uploaded to pexels.com as free to use

Leave a comment